NASA’s Voyager spacecraft have revealed a blazing 50,000° plasma barrier at the edge of our Solar System, overturning decades of assumptions, exposing a violent protective frontier against interstellar radiation, and leaving scientists both awestruck and urgently questioning the forces shaping our cosmic neighborhood.

In an astonishing revelation that has sent ripples across the astrophysics community, NASA’s Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft have confirmed the existence of a colossal plasma “firewall” at the edge of our Solar System, reaching a blistering 50,000 Kelvin—a temperature hotter than the surface of most stars.

This discovery, derived from data collected during Voyager 1’s heliopause crossing in 2012 and Voyager 2’s in 2018, overturns decades of theoretical assumptions that depicted the outermost boundary of the heliosphere as a cold, empty void.

Instead, the edge of our Solar System is now understood as a violent, high-energy transition zone that shields the inner planets from interstellar radiation, cosmic rays, and galactic winds.

The anomaly was first detected when Voyager 1 passed 121 astronomical units (AU) from the Sun on August 25, 2012, and again when Voyager 2 crossed 119 AU in November 2018.

Mission scientists noticed that the plasma temperature suddenly spiked from approximately 30,000 Kelvin to 50,000 Kelvin as the spacecraft crossed the heliopause boundary.

Dr.Elena Vasquez, a lead researcher on the Voyager Plasma Science Experiment, remarked, “We expected a gradual cooling or stable temperature at the boundary, not this violent spike.

It’s as if the heliosphere has a protective plasma wall, violently energized yet perfectly tuned to shield the inner Solar System.”

The discovery has also shed light on the mechanical interaction between solar wind and the interstellar medium.

As the outward-flowing particles from the Sun collide with the incoming galactic winds, they create a turbulent compression region that seems to be responsible for the sudden heating.

Yet the density of the plasma remains astonishingly low—less than one particle per cubic centimeter—which explains why both Voyager spacecraft survived the crossing without sustaining damage.

Scientists now understand that the “wall” behaves like a massive, tenuous shield: intense in temperature but sparse enough to prevent destruction of any human-made objects passing through.

Another surprising aspect of this finding is the alignment of magnetic fields observed on both sides of the heliopause.

Data from Voyager revealed that the internal solar magnetic field and the external interstellar magnetic field run nearly parallel in the boundary region, a configuration that contradicts prior models that predicted chaotic, orthogonal orientations.

Dr.Kunal Mehta, a heliophysics expert at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, stated, “The parallel alignment is completely unexpected.

It suggests that there are forces at work in the outer heliosphere that we still don’t understand, potentially hinting at unknown plasma dynamics or magnetic reconnection processes at an interstellar scale.”

Voyager’s observations have also confirmed the “breathing” nature of the heliosphere.

Slight differences between Voyager 1 and 2’s heliopause crossings—121 AU versus 119 AU—indicate that the heliosphere expands and contracts in response to solar activity cycles and interstellar pressure.

This dynamic behavior suggests that the Sun’s protective bubble is far more flexible and reactive than previously imagined, adjusting its outer boundary according to both internal solar emissions and external galactic conditions.

The implications of these findings are profound for understanding space weather, cosmic radiation exposure, and the potential habitability of planets both within and beyond our Solar System.

A 50,000 Kelvin plasma barrier acts as a first line of defense, filtering out high-energy cosmic rays that could otherwise bombard Earth and neighboring planets, potentially affecting atmospheres, climate, and long-term biological evolution.

“It’s a cosmic firewall,” Dr.Vasquez explained.

“Without it, life as we know it might face far harsher radiation levels from the galaxy.”

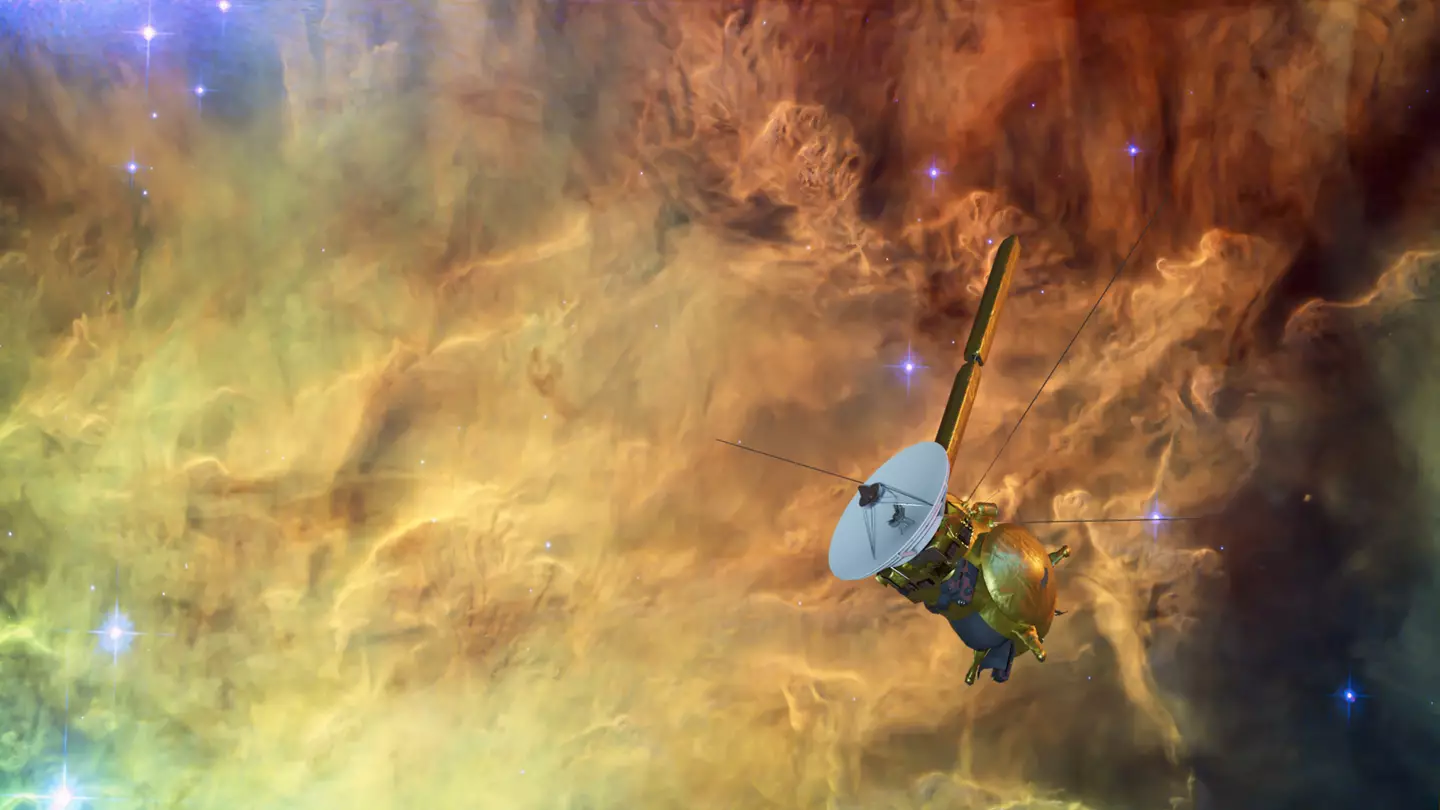

The Voyager missions, launched in 1977, were designed to explore the outer planets but have since become humanity’s farthest-reaching eyes in space.

Voyager 1 and 2 now serve as interstellar probes, sending invaluable data back to Earth despite being more than 40 years into their journeys.

Engineers are closely monitoring the spacecraft’s radiogenic thermoelectric generators (RTGs), which are expected to cease functioning by 2030, potentially ending direct measurements from the boundary regions for the first time in history.

Beyond immediate scientific curiosity, the discovery of the 50,000 Kelvin plasma barrier highlights the need for future interstellar missions capable of probing the heliopause in even greater detail.

Researchers are already discussing designs for new spacecraft that could survive and operate in this extreme environment, potentially unlocking more secrets about the interaction between our Sun and the galactic neighborhood.

NASA’s confirmation that the Solar System is encased in such a violent, energetic boundary challenges both theoretical astrophysics and our broader understanding of planetary protection.

It paints a vivid picture of the outer heliosphere as a living, dynamic shield, balancing between the internal push of solar wind and the relentless pressure of interstellar space.

As Voyager 1 and 2 continue their silent trek beyond the Sun’s influence, humanity gains an unprecedented view of the fierce, glowing frontier that guards our cosmic home.